Discovering more about Rainwater Basin wetlands

South of the Platte River in central Nebraska remain the nation’s only Rainwater Basin wetlands.

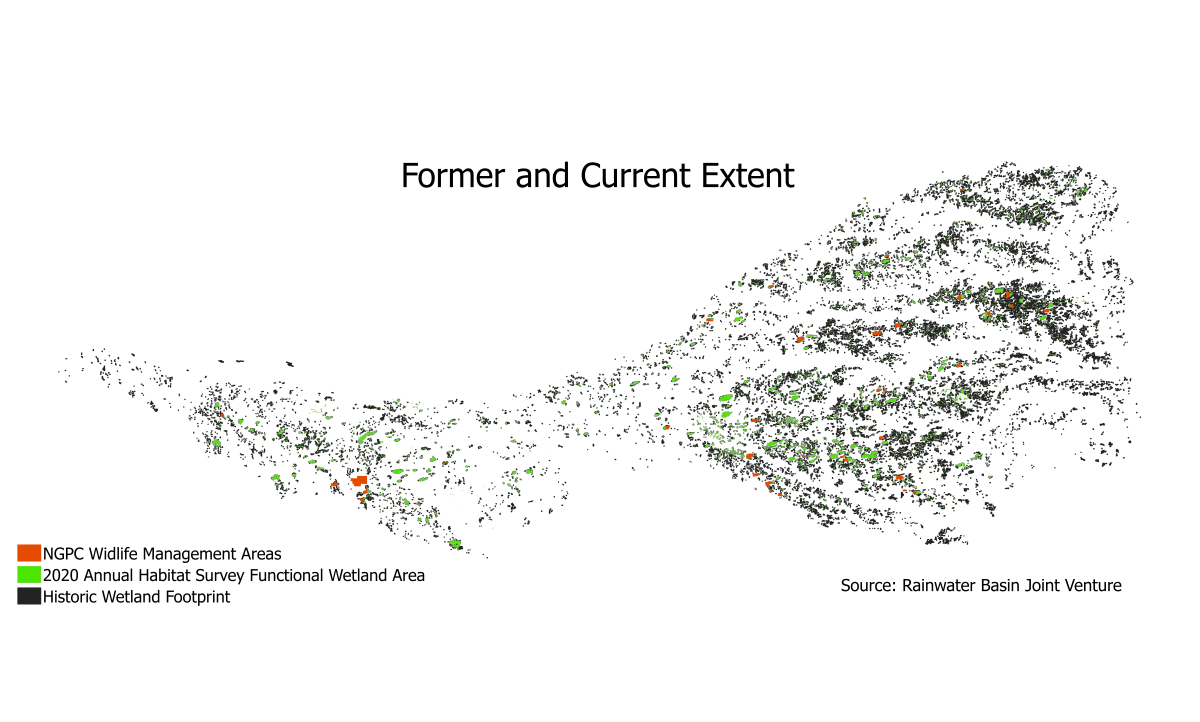

Although these wetlands once covered thousands of acres, scientists estimate only 10 percent of them still exist.

Little is known about the wetlands, but Sarah Thompson, an NRT master’s student in hydrology, is seeking to learn more about them and the best way to conserve them.

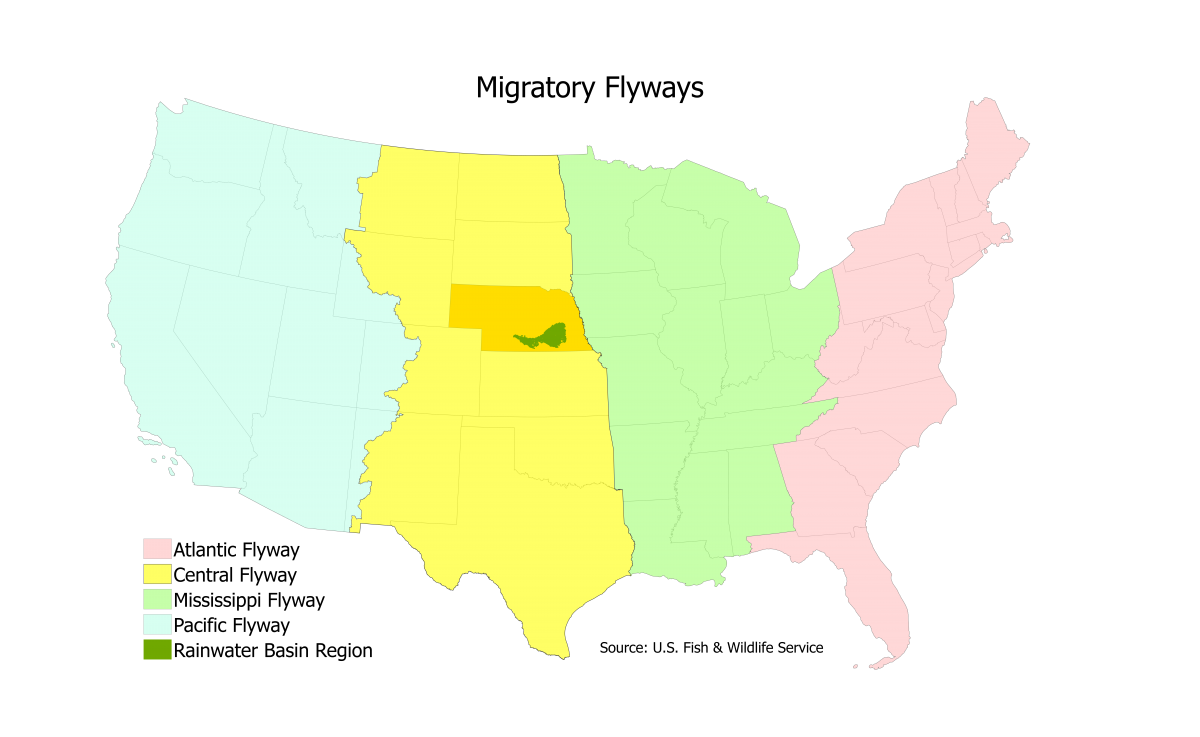

“The Central Flyway goes over these wetlands, and they are critical stopover habitat for migratory birds and waterfowl,” Thompson says. “Millions of birds pass over these wetlands every year while migrating. If you think about it, would you rather make a 16-hour road trip with no stops, or would you like to have at least one stop in the middle where you can sleep and get some food?”

She says the wetlands serve as habitat for other plants and animals as well and may help recharge the High Plains Aquifer and remove contaminants from water.

“Honestly, because they are so understudied, I feel like we don’t know the full importance of them,” Thompson says.

She is working with the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission, which owns 35 of the 100-or-so publicly owned Rainwater Basin wetlands.

To conserve and restore wetlands, governmental agencies remove sediment that has washed into the wetlands from surrounding croplands.

The wetlands have a layer of clay below them, allowing them to hold water. Excavators may remove only the top layer of sediment to preserve seed banks and protect the clay from punctures or drying out. Alternately, they may excavate down to the clay to eradicate invasive plants and increase holding area for water. Thompson is exploring which method works best at managing wetlands.

“I’m interested in what benefits excavation has, but I have to take into account all of these other variables that also influence the wetland, such as, most importantly, the amount of rain you get that year really has the most effect on how much water is in the wetland,” Thompson says. “Additionally, the size of the watershed or the soil type in the wetland affect how much water it holds. Land use in the watershed. What other restoration efforts have been taken for the area? So, essentially, it’s like having 40 independent variables and one dependent variable, the functional area of the wetland.”

She plans to compare the loss rate of water in wetlands with different excavation scenarios; for example, two wetlands with the same soil type but one has been excavated and the other not.

To gather such data, she placed sensors that measure water level every 10 minutes in six wetlands owned by the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. She had planned to install the sensors in 10 wetlands, but she and her advisor in the College of Arts and Sciences, Erin Haacker, found water in only six.

Rainwater Basin wetlands are ephemeral, meaning they naturally dry out and can be dry for years. This is just one factor that makes researching these wetlands tricky.

The researchers had to carry the PVC pipe in which the sensors would be installed, two fence posts and fencing (to build a fence around the pipe to keep cows from rubbing on it and knocking it over), a T-post driver weighing about 20 pounds, and a bag of tools through the wetland muck and water to where they could install the sensors to get a reliable water level reading.

Cows had walked through some of the wetlands, leaving deep hoofprints the researchers tried to step around to avoid tripping or sinking.

“In some places, there wasn’t a lot of plant material so you could see and walk around the hoof holes,” Thompson says. “In other wetlands, there was a lot of vegetation, so it was hard. Then you get to where the mud and water is, and it’s what I call ‘boot-sucking mud.’ If you just wear knee-high mud boots instead of waders, the mud will pull the boot off your foot. It’s very clay-rich, very sticky, and when you get out of the water, every step you take, you are sinking at least four inches because the soil is very soft.”

Thompson fell a couple of times but because the water was shallow and she wore waders, she was able to keep her upper torso dry. Still, the quicksand-like experience she had at one wetland was particularly unpleasant.

“We were in the middle of nowhere Nebraska, and if you stood in this wetland for an hour, you might be up to your thighs and you wouldn’t be able to get out,” she says. “And you can’t pull yourself out because there is just wet mud everywhere, and sometimes manure. Wetlands do not smell good.”

The sensors she and her advisor placed in the six wetlands cannot withstand freezing temperatures, so Thompson plans to remove them before winter and install more sensors in the spring.

“I’m definitely dreading going back out there, and I’m thinking about, when I go in the spring, what is it going to be like, because there is probably going to be more water, and it’s going to be colder,” she says. “Running around in the water in the summer is not that bad, but doing it when it’s cold, I’m like, ‘This is a labor of love.’”

Although the Rainwater Basin wetlands and their value have been studied less than Sandhills wetlands and southwest playas, Thompson suggests they could contribute to the resiliency of migratory birds far more than what is now known.

“If these rainwater basins cease to exist, that could have potentially a cascading effect,” she says. “You have all of these migratory birds that are migrating through the Central Flyway. If they don’t have this source of food and resting points, maybe fewer survive the trip or they arrive at their destination less healthy. There could be a series of declines in many species of birds that are what I guess you could call ‘international citizens.’”

Her concern for the environment and managing water in it responsibly is what she says attracts her to this work and the possibility of working for a governmental agency on environmental issues.

“Honestly, and this is going to sound weird coming from a hydrologist, I don’t even like water,” she says. “I personally don’t like being in water, and I also don’t like wetlands. They’re stinky and mucky, but they are just so important for the environment. It’s really coming to light lately how important wetlands are for water quality and for habitat and breeding grounds that, yes, I might have my personal issues with them, but for the love of the environment, I will do this.”

— Ronica Stromberg, NRT Program Coordinator