NRT students Daniel Rico and Christopher Fill have found that counting bats is far more difficult than counting sheep and it’s unlikely to put them to sleep anytime soon.

The two have been collaborating with Omaha’s Henry Doorly Zoo and Aquarium to devise a way to accurately count the fruit bats living in the zoo’s Lied Jungle. Egyptian fruit bats and Indian flying foxes have been soaring the skies of the Lied Jungle since it opened in 1992, but zookeepers have never had a precise count of the Egyptian fruit bats.

They know they have three Indian flying foxes, which are hard to miss with a body weight of about two pounds and wingspans that can reach more than three feet. Although the Egyptian fruit bats are smaller than this, they also outsize bats normally found in Nebraska, weighing in at 5 to 6 ounces and reaching two feet in wingspan.

Fill, who is studying bats in Nebraska for his master’s project, estimates the zoo’s Egyptian fruit bat population at 750, but the zoo would like a firm number. Since zoos now play a key role in conserving rare animal species, zookeepers strive to track animal populations to ensure their health. Nutritionists at the Omaha zoo have maintained their fruit bat populations with bananas, apples, oranges, melons and other fruits and a supplement called “bat gel” that provides additional nutrients.

“There are techniques that you could use to make sure you’re feeding the population regardless of your knowledge of the number,” Rico said, “but they still would like a hard and fast number if they could get one.”

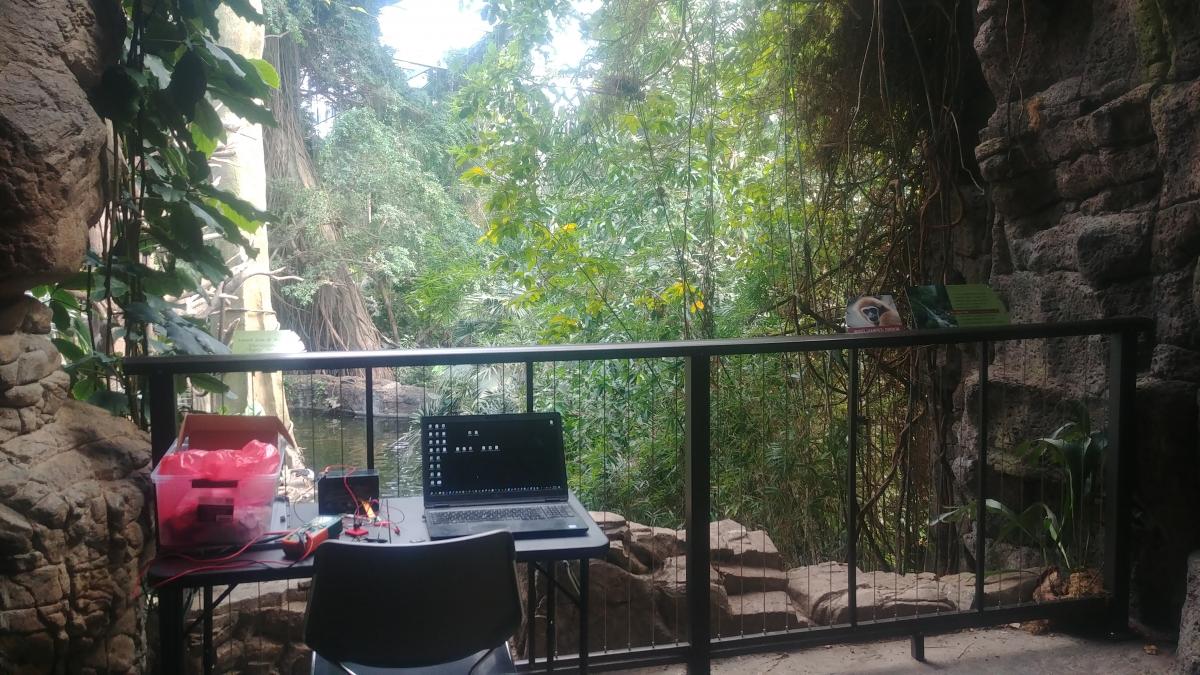

If only the zoo’s furry, fruit-munching residents would hold still! But the Lied Jungle stands eight stories tall and encloses wildlife exhibits over 123,000 square feet of floor space—plenty of room for bats to play hide-and-seek and blend into colonies hanging from cave ceilings and other places.

Complicating any census is the bats’ reproduction rate.

“They can reproduce twice a year,” Fill said. “Usually, it’s just one, but they might have twins, which can all throw things off.”

Fill possesses equipment used to detect bats from the calls they emit, but it can detect only the presence of bats, not their numbers.

In open country, he has used mist nets and harp traps to capture bats for tagging and counting, but he said this method could be stressful for the exotic bats and he would like a less invasive technique.

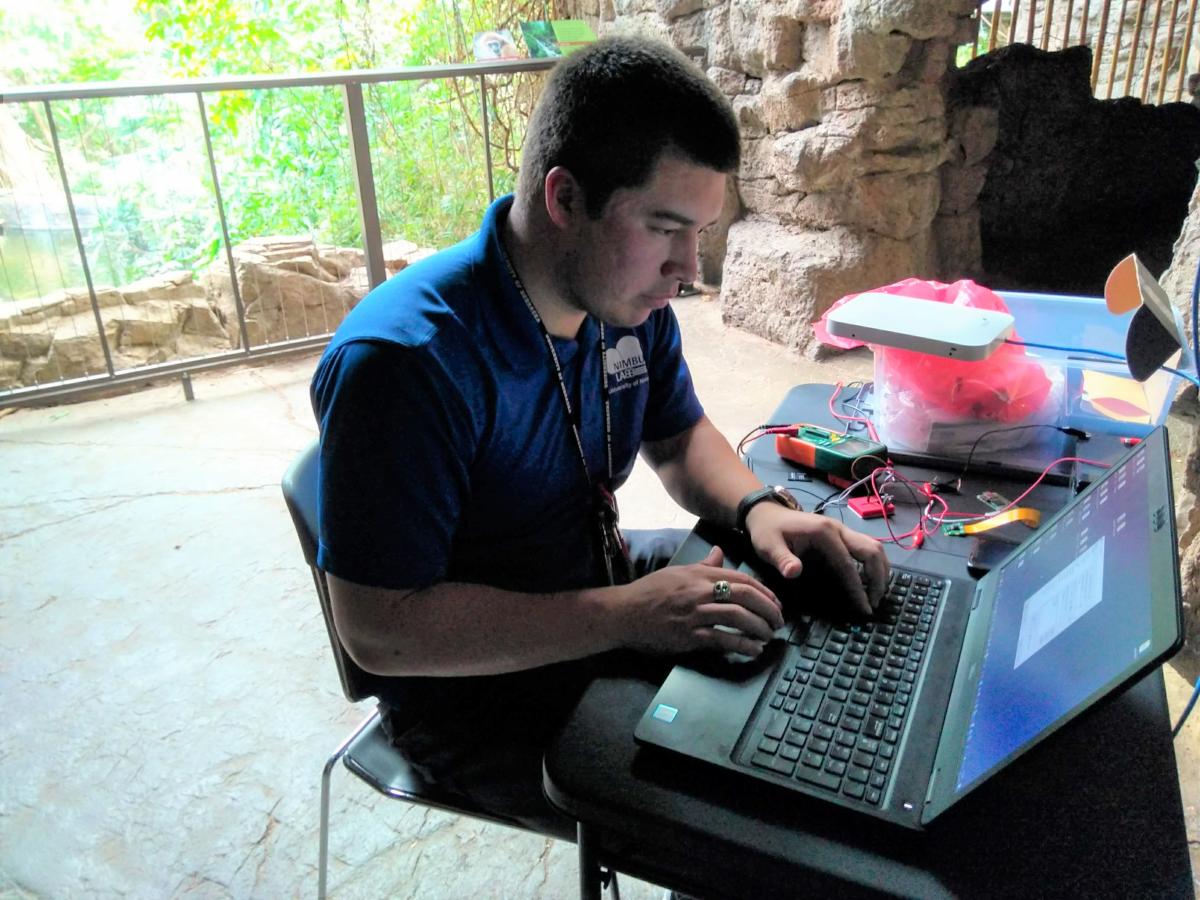

Enter Rico, a master’s student in Computer Science and Engineering with a background in Electrical Engineering, who has worked across disciplines with Fill and other NRT students to resolve ecological and environmental problems.

“What I am working on now is building a prototype for a synchronized imaging network,” Rico said. “So, since we know that the space the bats are in is finite, that means we can image a finite volume.”

Rico proposes to set up a network of 10 to 20 synchronized cameras—he hasn’t determined the correct camera to be used or how many yet—in the Lied Jungle. Each camera unit would be set up so that its field of view wouldn’t overlap with that of other cameras but, together, they would capture the bulk of the Lied Jungle.

“If you do image processing on those sets of images and you find bats in those images, they are unique individuals because these fields of view are all separate,” Rico said. “The bats can’t be in two places at once.”

The network of cameras would take images at set intervals over at least a few days and nights a week and especially at feeding times, when the bats are most active.

“The longer you do it, the probability goes up that you will eventually find all individuals,” Rico said.

He is building the first prototype now, which will likely be a unit composed of two cameras since they need to be synchronized.

“There are two aspects of this project,” Rico said. “There’s the hardware aspect, where you’re setting up the network and then the software aspect where you’re analyzing the images, looking for unique individuals, and then keeping a tally essentially.”

He said he wanted to use thermal cameras that would identify the bats by their body heat but high-resolution thermal cameras are too expensive. Instead, he is now seeking less expensive RGB/nIR cameras that will take high-resolution images to be fed through an image-processing algorithm able to key in on the brown colors of the Egyptian fruit bats and tally their numbers. The software should go through all of the synchronized images and find the highest total of bats found at any one time.

If Rico, Fill and the zoo succeed in this collaboration, the synchronized imaging network holds possibilities of being used in other enclosures to tally endangered butterflies and other species without risk or stress to the animals.

Everyone will sleep better then.

— Ronica Stromberg, National Research Traineeship Program Coordinator